Tomorrow marks the 150th anniversary of the start of the battle of Gettysburg. The battle here marked the turning point in the War Between the States (or American Civil War). Confederate forces under General Lee never again ventured into Northern territory after this battle.

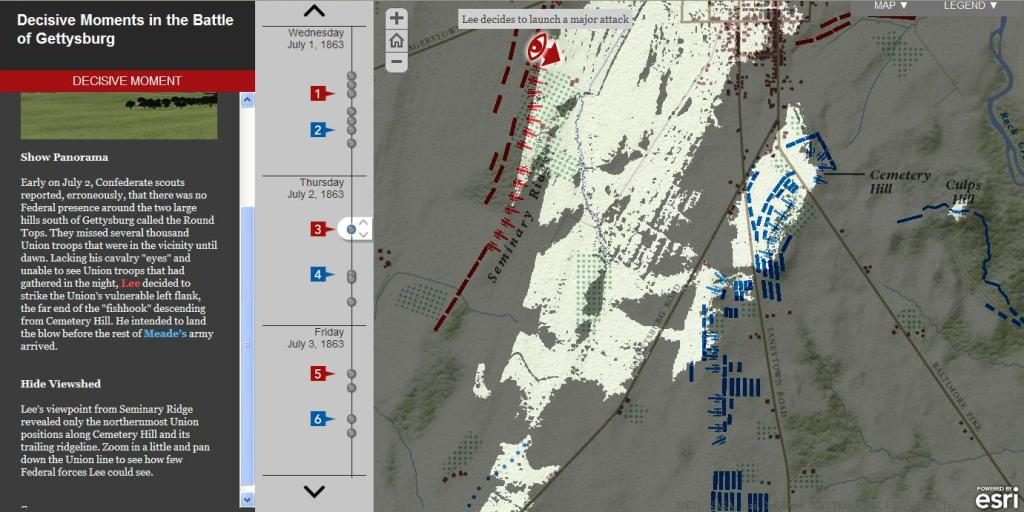

On the second day of the battle, General Lee ordered an attack on the left wing of the Union line. Erroneous scouting reports said that there were no Union forces on either Big or Little Round Top. Lee, in essence, started the attack with erroneous information and with what he himself could see of the Union Army.

A team led by geographer Anne Knowles of Middlebury College has created new interactive maps of the battle and the battle terrain for the Smithsonian Institute to commemorate this anniversary.

Knowles had this to say in an interview about the project:

“Our goal is to help people understand how and why commanders made their decisions at key moments of the battle, and a key element that’s been excluded, or just not considered in historical studies before, is sight,” Knowles said.

Long before the advent of reconnaissance aircraft and spy satellites, a general’s own sense of sight — his ability to read the terrain and assess the enemy’s position and numbers — was one of his most important tools. Especially at Gettysburg, where Lee was hampered by faulty intelligence.

“We know that Lee had really poor information going into the battle and must have relied to some extent on what he could actually see,” Knowles said.

The geographer applied GIS to find out what Lee could see and what he couldn’t.

To reconstruct the battlefield as it existed in 1863, researchers used historical maps, texts and photos to note the location of wooden fences, stone walls, orchards, forests, fields, barns and houses, as well as the movement of army units. High-resolution aerial photos of the landscape yielded an accurate elevation model. All of it was fed into a computer program that can map data.

Lee is believed to have surveyed the battlefield from a pair of cupolas, one at a Lutheran seminary and the other at Gettysburg College, both of which yielded generally excellent views.

But a GIS-generated map, with illuminated areas showing what Lee could see and shaded areas denoting what was hidden from his view, indicates the terrain concealed large numbers of Union soldiers.

A screen cap of this map showing what Lee could and couldn’t see is below. The gray areas indicate what was hidden from Lee’s sight by the topography of the battlefield as he looked down from Seminary Ridge.

I think the Smithsonian has done a great service with these interactive maps as they lead to a greater appreciation of the decision making by both Confederate and Union generals at this battle. The interactive map can be reached here.