Memorial Day is set aside to remember those men and women who died while serving our country in the armed services.

A recent family reunion and subsequent visit to my father’s grave got me to thinking about those who didn’t die while on active duty but who had significantly shortened lifespans due to their military service.

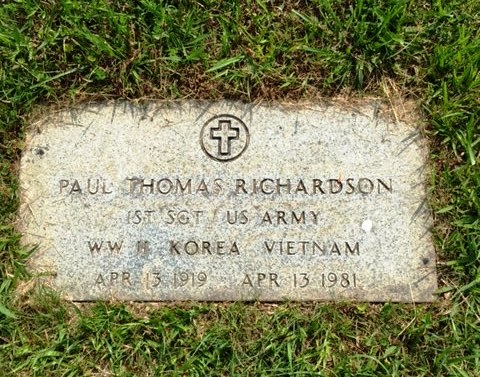

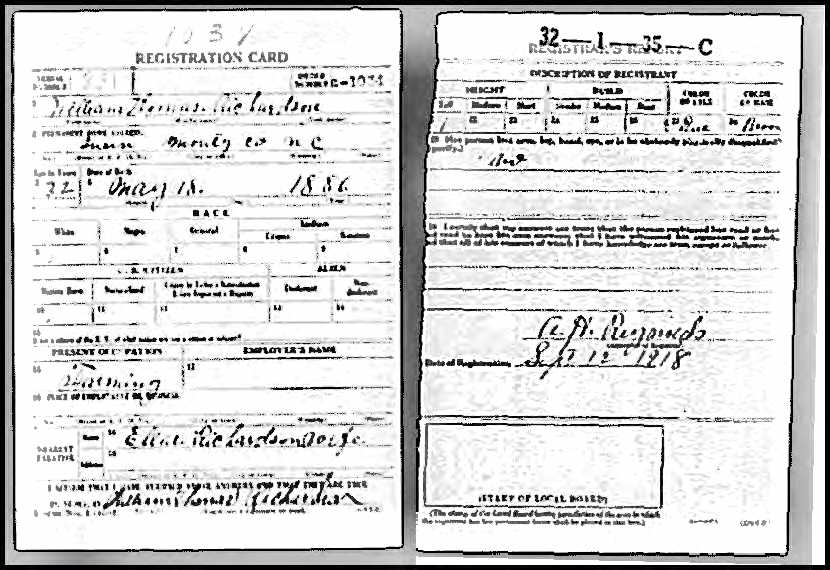

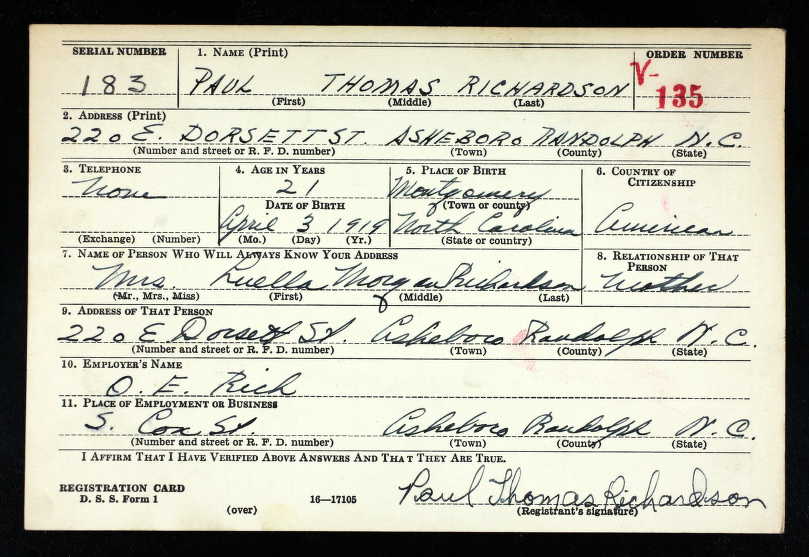

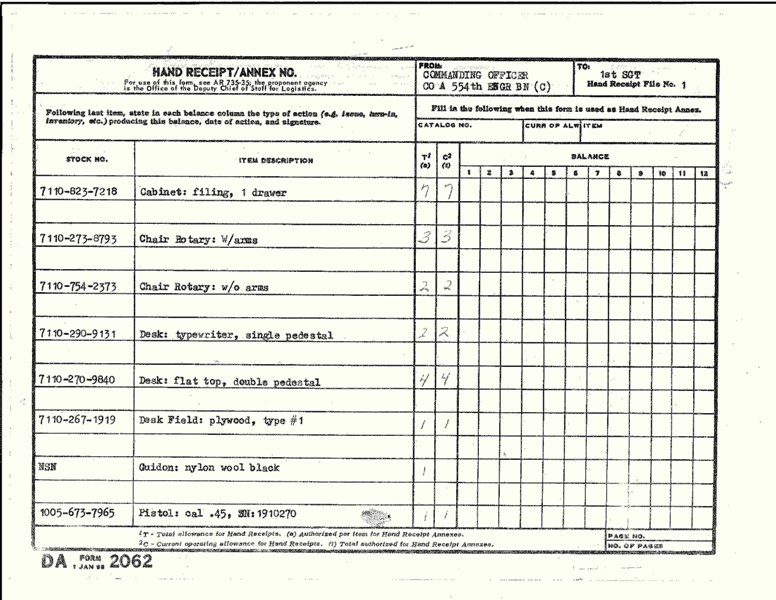

My dad was medically retired with 60% disability after 28 years of active duty service in the US Army. According to his DD 214, the effective date of his retirement was April 14, 1972. This was approximately a year after he returned from Vietnam on his second tour of duty there. I should be clear that my dad’s medical retirement was not due to combat-related injuries but rather due to angina, ulcers, and other maladies. These are typical stress-related illnesses.

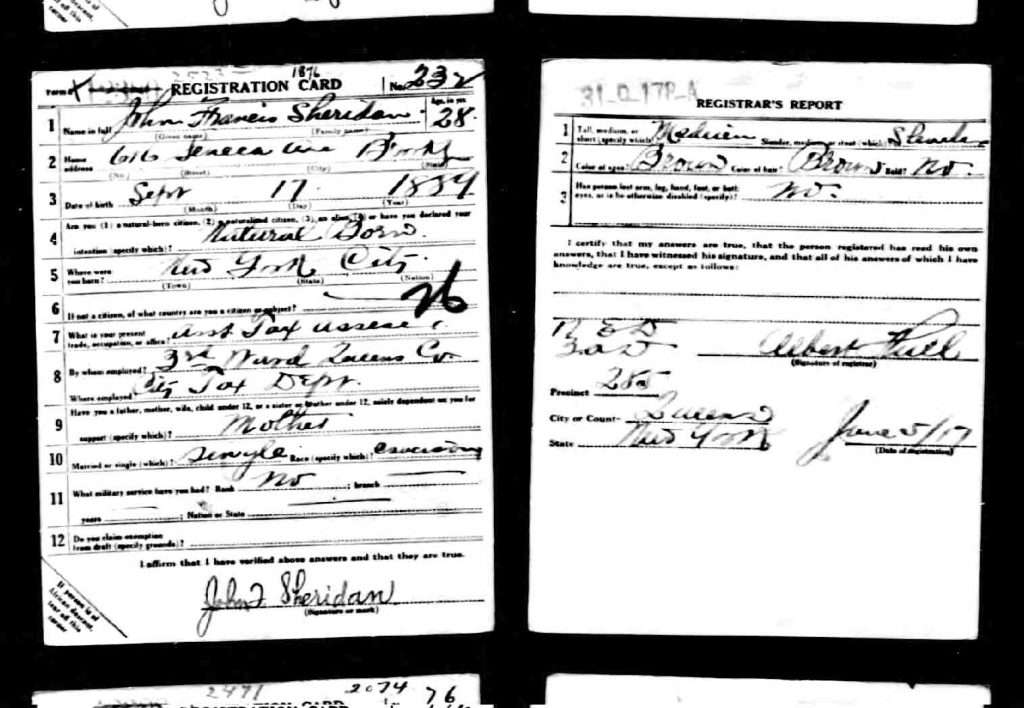

As you can see from the headstone, my dad died eight years and 364 days after he was retired from the Army. He had turned 62 just days earlier. (The date of birth on the headstone is erroneous – it should be April 3, 1919).

According to studies done by Department of Defense actuaries, active duty retirees have a higher mortality rate than do their reserve component peers. This disparity increases for enlisted retirees as compared to officers. The study was done on non-disabled retirees who were age 60 plus.

Defense officials haven’t done a study to explain death rate differences among military retirees. Speculation centers on stresses of full time service including past wars, frequent moves, constant physical activity to stay in shape, and stress-induced habits such as smoking and alcohol consumption…

Tom Bush, a senior policy official for reserve affairs, suggested to the board last August that more active duty retirees might have used tobacco or alcohol more often than did reservists. Hartnedy suggested post-traumatic stress might be a factor, even controlling for VA-rated disabilities.

“I would think that kind of mental strain” from years on active duty “would have an impact…very long term, after retiring,” he said.

As to the suggestion that active duty retirees might have “used tobacco or alcohol” more often, it was common and it was expected that you drank and smoked. Cheap booze and cheap cigarettes were the rule in the Army of the 50s, 60s, and 70s. It was a part of the culture and I think stress was a contributing factor to overuse.

My dad arrived in Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam at the age of 48 in 1967. He returned to Vietnam in 1970 at the age of 51. He was a middle-aged man with white hair. While he never complained of it being stressful, I imagine it had to be especially since it was hard to distinguish friend from foe. Even though he served in what was essentially the rear echelon, it was still a war zone.

I think about all of those more recent veterans who have served in either Iraq or Afghanistan or both. Just like in Vietnam, the front lines are blurred. Even if they weren’t injured in an IED explosion or a suicide bombing, the possibility was there. I think the actuaries and epidemiologists will have their hands full in years to come conducting studies on these vets. I have to wonder how much their life expectancy has been shortened by their military service.

So on this Memorial Day, let’s remember all of those who died while in service to our country. Let us also remember those who, while not dying in active service, died a lot sooner than they should have.