It is hard for me to believe it has been almost 80 years since Allied forces landed on the beaches of Normandy to begin their march towards Germany. As I was born a little less than 13 years after the landing, it was still fresh in the minds of many. Today, not so much. Most of the veterans of that day have now passed away.

Some of the most enduring scenes from that day were pictures taken by famous photographer Robert Capa on Omaha Beach. Most of his photos were lost due to errors in processing.

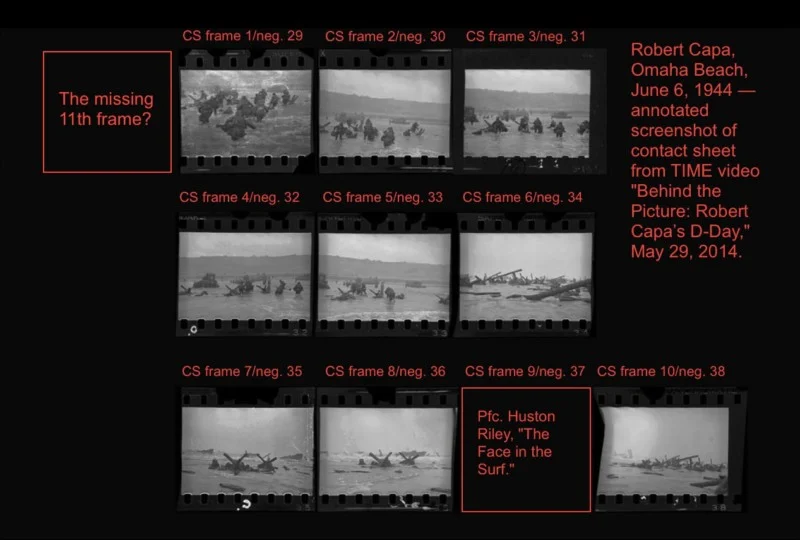

Actually, it turns out that much of that story was a myth. It laid the blame on a novice film processor who overheated the negatives in a drying box to the point that the emulsion melted. All that was left were the 11 frames above.

From PetaPixel debunking the myth:

In retrospect, I cannot understand how so many people in the field, working photographers among them, accepted uncritically the unlikely, unprecedented story, concocted by Morris, of Capa’s 35mm Kodak Super-XX film emulsion melting in a film-drying cabinet on the night of June 7, 1944.

Anyone familiar with analog photographic materials and normal darkroom practice worldwide must consider this fabulation incredible on its face. Coil heaters in wooden film-drying cabinets circa 1944 did not ever produce high levels of heat; black & white film emulsions of that time did not melt even after brief exposure to high heat; and the doors of film-drying cabinets are normally kept closed, not open, since the primary function of such cabinets is to prevent dust from adhering to the sticky emulsion of wet film.

No one with darkroom experience could have come up with this notion; only someone entirely ignorant of photographic materials and processes — like Morris — could have imagined it. Embarrassingly, none of that set my own alarm bells ringing until I started to fact-check the article by Baughman that initiated this project, close to fifty years after I first read that fable in Capa’s memoir.

The PetaPixel article by A. D. Coleman is rather long but well worth the read. It is meticulously researched and documented. Myth has its place but documenting the reality of what really happened is more important.

I wasn’t around during the ’40s and haven’t handled any B&W film from that era.

But I was processing B&W film, by hand, in the ’90s, and I don’t imagine much changed in that time. (If it ain’t broke, and all that.)

A film drying cabinet doesn’t produce high heat. At best, it’s a low-to-moderate amount of heat and a bit of airflow (think: tumble-dry-low on your clothes dryer — it’s not “hot” by any means, more like a pleasant warmth), and as the quoted section said, the doors are closed not to retain heat, but to keep dust off the negatives as they dry.

While it’s possible the cabinet was malfunctioning and producing high heat, that’s something that would be noticed and fixed right away, especially if the technicians are processing multiple rolls at a time. It’s hard to believe that would happen on this particular roll of film (out of how many hundreds of other rolls being processed?), harder to believe that it would be enough heat to destroy film rather than just causing some blurriness and “fog”*, and even harder still to believe it would only affect a few frames here and there rather than burn/melt the whole roll.

I agree, the “official” story raises some red-flags.

Just my semi-learned, non-expert opinion.

———

* – RE: “blurriness and fog”: The scene being recorded was an active water landing through ocean surf. There’s GOING to be blurriness and fog; blurriness because everything is in motion — it’s impossible to keep perfect focus — and fog because “ocean surf”. It’s unlikely anyone would notice a little extra from processing, over what was already there from the scene itself.

Also, a “contact sheet”, for those unaware, is when a photographer/developer will lay the developed strips of negatives directly on the photo paper (hence, “contact”), lay a sheet of glass on top to hold the negatives flat, and expose it to light. This creates a “reference” sheet of images directly from the film (e.g. 35mm film makes 35mm images), in order, exactly as they were taken — no enlarging or cropping. Often the photographer will examine the contact sheet with a magnifying glass to decide which frames are worth enlarging into full-size images.

On that “annotated screenshot of contact sheet”, the “missing 11th frame” wouldn’t be where it is, but off to the right of the bottom row. (Frame 9, “The Face in the Surf”, is a copyrighted image, so it’s not shown.)

Still amazing even if only 11 photos for whatever reason.

IIRC, it was Capa himself who said a tech ruined the film. Lately, I’ve seen speculation that he was so overwhelmed on the beach that either he ruined the shot or forgot to take more. We’ll never know but those photos are haunting.